Why worry about trade deficits?

Should we be concerned about the U.S. running a trade deficit?

President Trump claims the U.S. is being “ripped off” by nations that impose tariffs on U.S. imports. In his address to Congress, he said, “Whatever they tariff us, we tariff them. Whatever they tax us, we tax them.” “A lot of them are globalist countries and companies that won’t be doing as well because we’re taking back things that have been taken from us many years ago.” He has referred to April 2 as “liberation day,” when he plans to announce tariffs on 10 to 15 countries that account for the recent $1.2 trillion U.S. trade deficit.

There aren’t many logical reasons for imposing across-the-board tariffs on all imports from a given country or reciprocal tariffs on all countries that impose tariffs on U.S. imports. Tariffs are generally used to protect specific sectors of economies from foreign competition. Tariffs may protect new or emerging economic sectors of domestic economies and maintain domestic production of goods and services essential for economic sovereignty, such as agricultural production. Nations often accept tariffs on their exports to maintain long-term beneficial trade relationships with other countries. In all these cases, tariffs are selective rather than across-the-board or reciprocal.

The likely reason for Trump’s across-the-board tariffs is to impose higher taxes on U.S. imports to help offset further cuts in income taxes. In this case, being “ripped off” would simply be an excuse for increasing one kind of tax to help offset the effects of reducing another. However, if across-the-board tariffs trigger a global trade war, there is no assurance that tariffs will generate more tax revenues than they destroy. Trade wars of the early 1900s led to the Great Depression.

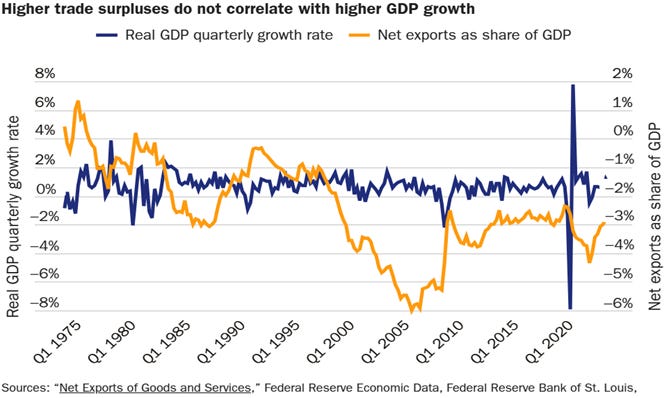

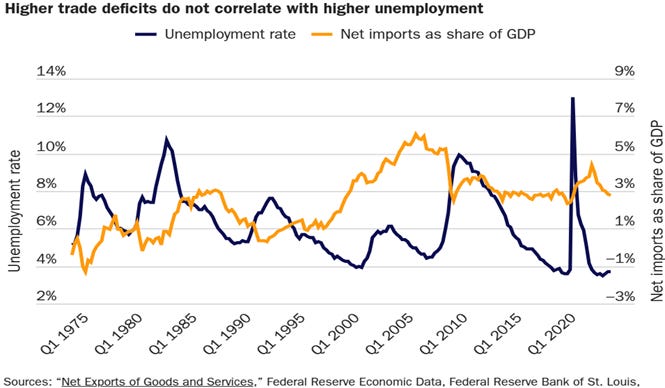

A more defensible reason for increasing tariffs would be concerns about the U.S.’s persistent trade deficits or negative balance of trade. However, there is no historical correlation between trade deficits and either unemployment or growth in the U.S. economy. U.S. trade deficits have accounted for only 2% to 4% of the gross domestic product, or GDP, and any impact would have been small. The U.S. has had arguably the strongest economy in the world over the past 50 years despite trade deficits. Only China has grown faster. So, why should we be concerned about running a trade deficit?

The U.S. trade deficit since the 1970s has been in “goods” rather than “services.” The term “goods” refers to tangible, physical items, including manufactured products (automobiles, textiles…), agricultural commodities (corn, soybeans, pork…), and other physical assets (petroleum, minerals…). The primary concern has been the loss of manufacturing in the U.S. to countries with lower labor costs. Trade deficits in manufacturing goods have more than offset typical surpluses in agricultural and petroleum products. Recently, however, the value of imports of food products has exceeded the value of exports of agricultural commodities.

The term, “services,” in international trade refers to intangible activities, including transport (air, sea, land), travel (tourism, education…), financial services (banking, insurance…), telecommunications (internet, satellite…), and professional services like consulting, accounting, and legal services. The U.S. has run a consistent trade surplus in services since the 1970s. Some refer to a shift in the U.S. economy from manufacturing to a service economy. However, the growth in service exports had not been fast enough to offset increasing imports of manufactured goods.

The U.S. trade deficit is shown as the “current account” in Chart 1. The deficit has recently averaged above $3 billion per quarter, or $1.2 trillion yearly. Primary and secondary income balances in Chart 1 reflect the flow of money between residents and non-residents: primary income (wages, interest, dividends…), and secondary income (money sent home by foreign workers, foreign aid…). The deficit in secondary income has more than offset small surpluses in primary income.

Despite concerns about the impacts of trade deficits on the U.S. economy, there is little evidence that net imports, or the trade balance, has a measurable effect on the GDP. If there were a correlation between trade deficits and GDP, the two lines in the chart below would move up and down together. The economy would grow more slowly when trade deficits (negative net exports) were large and grow faster when the trade balance improved. There has been little, if any, indication of such a relationship since 1970.

In fact, there are logical reasons to believe that growth in the U.S. economy may have contributed to the persistence of trade deficits. Fixed exchange rates among international currencies were abandoned in the early 1970s. This allowed the exchange rates among different currencies to fluctuate. Since then, the strong U.S. economy has generally kept the value of U.S. dollars high relative to other currencies. This has made U.S. goods more costly to foreign buyers and imports less costly to U.S. consumers.

The consistently strong U.S. dollar has also been accepted as the world's reserve currency or currency most likely to maintain its value. This means other countries need U.S. dollars for their international transactions and investments. So, foreign traders and investors use U.S. dollars resulting from trade surpluses to buy U.S. Treasury Securities, similar to holding time deposits of U.S. dollars. The foreign debt that so many people seem to worry about is a natural consequence of the U.S. dollar’s acceptance as the world’s reserve currency, not an inability of the U.S. government to finance its deficit spending.

Another reason for trade deficits is that U.S. consumers tend to spend more and save less than consumers in other countries, which includes buying imported goods. Again, consumer spending may be as much a matter of optimism about the stability of the U.S. economy and their ability to continue earning and spending, as a lack of financial discipline. Taxes are also lower relative to the GDP in the U.S. than in most other so-called developed nations, which means U.S. consumers have more money to spend and more need to spend it on things that may be imported.

Even if trade deficits negatively affected the overall economy, their impacts would likely be small. Trade deficits and surpluses historically have averaged only 2% to 4% of the GDP. The only time the U.S. has experienced a persistent trade surplus was in the late 1800s and early 1900s. This was a time of increasing agricultural production, rapid expansion in manufacturing, and a boom in U.S. oil exploration and petroleum production. Before 1870 and after 1970, the U.S. consistently ran trade deficits, but has nonetheless experienced persistent economic growth.

There is likewise little evidence of a negative impact of net imports on overall U.S. employment. If there were a negative correlation between net imports and unemployment, the two lines in the chart below would tend to move in opposite directions. Unemployment would rise whenever net imports decline, meaning trade deficits increase. Since 1970, higher unemployment has occasionally been associated with large trade deficits, but the two more often have moved in the same direction or have shown no relationship to each other.

So if trade deficits have not affected economic growth or employment, why should we be concerned about the U.S. trade balance with other countries? The most important reason is that the impact of deficits has not been felt evenly across the U.S. economy. Manufactured goods account for about 10% of the U.S. economy, but nearly all the 2% to 4% total U.S. trade deficit is associated with manufacturing. This means about one-fourth to one-third of all manufactured goods sold in the U.S. are imported. We should be concerned about the impacts of trade deficits on the manufacturing workers displaced by the shift in the U.S. economy from manufacturing to a service economy.

Tariffs might or might not have been a logical strategy for protecting workers during the transition. However, the U.S. needs to either restore its comparative economic advantage in manufacturing or develop another sector, or other sectors, of the U.S. economy to provide quality employment opportunities for the displaced factory workers and similar workers of the future. Tariffs are not a solution to problems caused by a structural change in the U.S. economy.

The economy, even if working perfectly, responds to our needs and wants as consumers, not as workers or members of society. If workers in other countries have fewer economic opportunities and thus are willing to work harder for less, imposing tariffs on imports is not a long-term solution. Higher prices resulting from tariffs will simply accelerate the trend toward automation, artificial intelligence, and other digital technologies, displacing even more U.S. workers.

We see the negative impacts in rural America today of the failure of the U.S. government to consider the displacement of family farmers. Changes in technologies and accommodating farm policies in the 1960s and 1970s brought about a transition from family farms to industrial agriculture. The appropriate response in this case would have been a change in farm policies to ensure the ecological and social integrity of agriculture, once the negative impacts of industrial agriculture became apparent. A shift in policy priorities to quality and nutrition, rather than quantity and price, would have benefited farmers and consumers alike. There would also have been more quality employment opportunities in rural America and more vibrant and prosperous rural communities. Instead, displaced family farmers were left to rely on social welfare programs, and rural communities were left to wither and die.

We see the negative impacts in economically depressed urban communities today of the failure of the U.S. government to consider the displacement caused by the shift from manufacturing to a service economy. Perhaps a change in government policies to ensure the ecological and social integrity of U.S. manufacturing, even now, would result in premium market prices for U.S. products in world markets that would more than offset the higher salaries and wages for U.S. workers. Regardless, increasing prices of imported products is not a long-term solution to the loss of manufacturing jobs in the U.S. or the persistent U.S. trade deficit, and it’s not an acceptable excuse to raise taxes.

Trade among sovereign nations allows each nation to benefit from its comparative economic advantages and also to benefit from the comparative economic advantages of its trading partners. It’s like two, three, or four people working together, each doing what they do best for themselves and others while realizing the added benefits of what the others can do better. Each is free to choose what they do and don’t do; they are sovereign individuals. However, they are committed to working together for their common good rather than trying to take advantage of each other. Regardless of the rationalization, reciprocal tariffs and trade wars are not a logical way to benefit from international trade.

John Ikerd

Links:

https://www.yahoo.com/news/trump-claims-us-being-ripped-165513970.html

https://www.yahoo.com/news/why-donald-trump-referring-april-031206460.html

https://www.oecd.org/tax/revenue-statistics-united-states.pdf

https://www.stlouisfed.org/on-the-economy/2020/february/us-rise-trading-services#:~:text

https://www.bea.gov/news/blog/2024-02-07/2023-trade-gap-7734-billion#:~:text

https://hbr.org/2018/07/why-the-u-s-trade-deficit-can-be-a-sign-of-a-healthy-economy?

https://www.bea.gov/data/intl-trade-investment/international-transactions

Many writers like this one are reacting to Trumps tariffs with an emotional belief that trade with another is a god given right ..which it is not.

They are also stuck in the “free trade only” solutions mode and have not bothered to look at history, or understand the concept of value rather than activity in an economy..

Well things are changing…..

Economists are mixed on if Global free trade is viable.

I attach my Substack article on the subject

https://nigelsouthway.substack.com/p/does-the-usa-need-usmca

And also a short article that describes what is now called the Productivism Paradigm by Dani Rodrik, a leading economist,. This is Trumps agenda..

The new productivism paradigm? - CGTN

https://news.cgtn.com/news/2022-07-06/The-new-productivism-paradigm--1brjj1feoVO/index.html

The old thinking was that comparative advantage was always good… but there were conditions for it to work that have been forgotten.. …Capacity can always be filled, and the wealth gradient must be close to equal… but in the global trade environment we still have 2B people underemployed and a huge wealth gradient between the west and the rest which was a problem for the west in the global free trade and people migration debacle of the last 30 years. Tariffs are a useful device to force localization ..

More on this if you want on my Substack.

Thank you for sharing. This is a most excellent article