Why should we care about competitive markets?

Why should the government break up monopolies and oligopolies?

You don’t need to be an economist to know that fewer and larger corporations are dominating markets for more and more products and services. Google controls more than 85% of the market for internet search engines. Kellogg, General Mills, and Post control over 80% of the market for cold cereals. Three airlines, American, Delta, and United, control nearly two-thirds of air travel in the U.S. Starbucks and McDonald's have more than 60% of the retail coffee market. Some large corporations, like Coca-Cola and Hershey, own dozens of different retail brands, creating the illusion of competition that does not exist.

Why should we be concerned about how few corporations control how much of specific markets? We can find what we are searching for with Google. There are dozens of different cereals in supermarkets. Airfares have risen far less than overall inflation. We don’t have to drink high-priced coffee unless we choose to. And, we can still buy our favorite soft drinks or candy, so who cares what corporation owns the brands?

Why should we care if one corporation controls an entire sector of the economy, or has a monopoly, or, more commonly, if three or four corporations share control of a market, which is called an oligopoly? If corporate consolidation doesn’t cause prices to rise or the quantity and quality of products to go down, or stifle innovation, does it really matter how many firms control a particular sector of the economy?

It matters because in capitalist economies, markets need to provide incentives to produce “the right stuff,” not just more “cheap stuff.” The only way to ensure that market economies produce things that meet the real needs and preferences of consumers is to maintain economically competitive markets. In economics, “competitive markets” means there is a large enough number of small enough sellers to ensure that no seller, or a small number of sellers acting together, can significantly influence the overall availability of products or market prices.

A larger number of smaller firms is necessary to ensure that retail prices reflect consumers’ preferences and that higher or lower prices are passed on to producers as incentives to produce what consumers need and want, rather than retained as excess corporate profits. The excess profits of too few and too large corporations result in less production of things that benefit consumers, and more production of things that generate profits for corporate executives and shareholders.

In industries dominated by a few large firms, it’s difficult, if not impossible, for someone with a better idea, product, or service to start a new business. New businesses that threaten the status quo are denied access to markets, or are bought out or forced out of business by their deep-pocketed corporate competitors. Large corporations have the power to convince consumers they have access to the widest possible assortment of the best products at the lowest possible prices, and that claims otherwise are false or misleading. Too few and too large corporations stifle innovation and limit consumers’ choices.

Successful start-up businesses are limited primarily to markets that did not previously exist and thus are not yet dominated by a few large firms. Apple, Microsoft, and Google had no established competitors to beat in gaining control of markets for microcomputers, cell phones, and search engines. Once these dominant corporations were established, new entrants found it virtually impossible to succeed in their respective markets. There is no incentive to reduce prices or innovate, at least not more than necessary to maintain their dominant market share. Consumers never have an opportunity to choose products or services that would have been offered by those unable to gain access to markets.

The only means of ensuring that we are getting the “right stuff” to meet our needs and preferences is to maintain a sufficiently large number of sufficiently small providers. If individual or small groups of corporations can influence market prices or other conditions of trade, they have “market power.” If corporations have market power, sooner or later, they will use it to maximize profits by exploiting consumers.

Corporate consolidation has long been considered a threat to the U.S. economy. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 was enacted to prohibit monopolies and other combinations that restrain trade. Standard Oil and American Tobacco controlled more than 90% of their respective markets at the time. The Sherman Act allowed the government to break up large corporations, such as Standard Oil, but the act proved difficult to enforce. John D. Rockefeller (oil), Andrew Carnegie (steel), Cornelius Vanderbilt (railroads), and J.P. Morgan (financier), known as the “robber barons,” continued to consolidate corporate power and dominate their respective industries. The Clayton Antitrust Act was passed in 1914 to strengthen the Sherman Act and prohibit anticompetitive practices, such as collusion, price fixing, and discriminatory pricing.

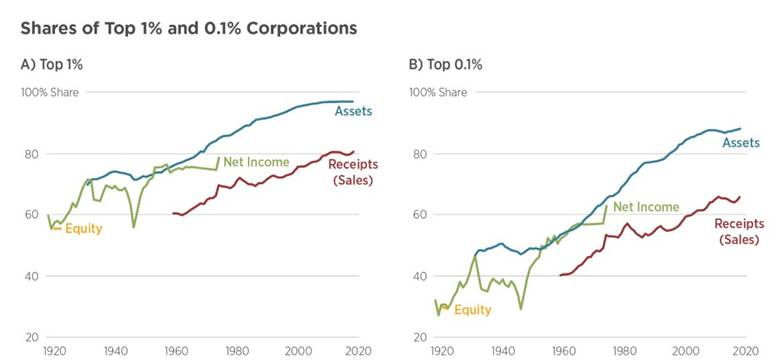

These antitrust laws have continued to be enforced, with varying degrees of commitment, by the Department of Justice, the Federal Trade Commission, and, in cases involving livestock and poultry marketing, by the Department of Agriculture. Obviously, the enforcement has been ineffective, as verified by the continued consolidation of market power and the current lack of economically competitive markets. Since the early 1930s, corporate shares or stock in the top 1% corporations have increased by 27 percentage points (from 70% to 97%) and the top 0.1% by 40 percentage points (from 47% to 88%).[i]

The trends toward greater corporate concentration of economic and political power have not been significantly affected by changes in antitrust policies or changes in political parties. The only signs of decline in the corporate consolidation were associated with the transition from a manufacturing to a service economy during the 1970s and 1980s. New corporations emerged to replace those displaced by the transition, and the upward trend in corporate consolidation of power continued.

Enforcement of antitrust law was essentially abandoned after 1979, when the Supreme Court adopted the “consumer welfare” standard for assessing proposed mergers. Approvals are based on whether a business practice or merger is expected to harm consumers by leading to higher prices, reduced output, or diminished quality of products or services. It no longer matters how few corporations control a market, as long as prices are not expected to rise, production is not expected to fall, and quality, which is difficult to measure, is not expected to deteriorate.

The typical argument in support of corporate mergers is that the larger resulting organization will be able to provide products or services at a lower cost to consumers by realizing economies of scale. Economies of scale result from being able to reduce production costs by operating a larger business or producing at a larger scale. The cost savings may come from spreading the high fixed cost of a production facility, such as an automobile plant, across more units of production, as with more automobiles produced per million dollars spent for the plant. Economies of scale may also result from spreading the high cost of a top management team across more production units or plants, as in banking and digital technologies. Such efficiencies exist, to one extent or another, in many sectors of the economy. However, if corporate consolidation significantly reduces competitiveness, the lower costs of production will not be passed on to consumers over time but instead retained as corporate profits.

The consumer welfare standard is based on an outdated concept of monopoly control of markets. Theoretically, monopolies increase profits by reducing production, which allows them to raise prices. Monopolies may also cut costs by reducing the quality or durability of products. The consumer welfare standard overlooks the fact that once corporations are allowed to gain a significant market share through consolidation, they can drive their weaker competitors out of business by lowering prices, increasing production, and promoting superficial improvements and innovations. Lower prices and increased production are then hailed as verification of competitiveness.

However, once a small number of large corporations gain control of a market, they tend to function as a “shared monopoly.” They increase their collective profits by raising prices, limiting production of less profitable products or services, and stifling innovation by competitors, all to the detriment of consumer welfare. Research has shown that once three or four large corporations share more than 40% of a market, they can coordinate their production and pricing decisions without necessarily violating antitrust regulations. They can function collectively much like a monopoly.”[ii] The four-firm market share for selected sectors of the agri-food industry is shown in the chart at the end of this post.

The consumer welfare standard also fails to recognize that when corporations gain market power, they gain political power. They gain the power to influence, or dictate in some cases, public policies. They not only stifle the enforcement of antitrust laws but also prevent or nullify regulations meant to protect the environment, ensure workers’ rights, or serve other legitimate public interests. Once corporations become “too big to fail” without disrupting the economy, they can be assured that the government will bail them out if their high-risk, high-profit ventures fail, as was the case with savings and loan banks in the 1980s and financial institutions in general during the Great Recession of 2008-2009. With virtually unlimited corporate financing of political campaigns, corporations have gained more political power than the real people.

The primary problem with the consumer welfare standard of antitrust enforcement is that it diverts attention from the existential threat to the sustainability of capitalist economies and democratic governments, including those in the U.S. Large multinational corporations have been allowed to gain the political power to prevent the implementation of government policies necessary to restore economic competitiveness to capitalist markets. Wealthy individuals, such as Musk, Zuckerberg, Bezos, and Ellison, have accumulated their wealth and political influence by creating and managing growing corporations. They are the “robber barons” of the 21st century. (Check out Austin Frerick’s book, Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption in America’s Food Industry.[iii])

The only solution to the problem of too few, too large corporations is to break them up into more, smaller corporations, and continue breaking them up until economic competitiveness is restored. There may be some tradeoffs between producing things most efficiently and producing the things consumers need and want—between “cheap stuff” and the “right stuff.” In cases where significant economies of scale exist, large corporations should be operated as investor-owned “public utilities.” Ownership could be private, but production, pricing, and other management decisions would be subject to government oversight and regulation to protect consumer and public interests. “Natural monopolies,” such as water, sewer, and electricity, are already managed as public utilities, and the concept could be extended to other sectors of the economy where significant economies of scale exist.

It may take an economic collapse to break the corporate grip on government. Once people regain control of their governments, however, they should never again allow corporations to grow large enough or few enough to destroy the competitiveness of markets or the integrity of politics. Under corporate control, the internet has become an information jungle, more than nine cents of each dime spent on dry cereal pay for processing, packaging, and advertising, air travel has become a test of patience and endurance, coffee that used to cost a nickel now costs two to five bucks, and candy bars are half the size and five times the price.

Electricity might have replaced gasoline in transportation decades ago if large petroleum producers had not been able to stifle competition. Sustainably produced foods might have replaced the industrial food system by the early 2000s if large agribusiness corporations had not been allowed to stifle innovation. High-speed rail might have replaced a million miles of crowded highways, in the absence of the objections by politically powerful corporations. We might not be facing the crisis of misinformation and disinformation if the internet were managed as a public utility with a clearly defined public purpose. We will never know what kind of world an economically competitive economy would have brought, because we allowed corporations to become too big and too few.

Adam Smith wrote of the butcher, baker, and brewer, “[H]e intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention.” The pursuit of economic self-interests, including corporate interests, is led by an invisible hand to promote the common good, only if there is a sufficiently large number of sufficiently small providers of goods and services. This was the situation in the time of Adam Smith. It is not the situation today. Adam Smith’s invisible hand has been mangled and disabled by unrestrained corporate consolidation. That’s why we should worry about the lack of competition. That’s why the government should, and ultimately must, break up monopolies and oligopolies.

John Ikerd

Endnotes:

[i] 100 Years of Rising Corporate Consolidation; https://bfi.uchicago.edu/insight/research-summary/100-years-of-rising-corporate-concentration/

[ii] A Special Report to the Family Farm Action Alliance by Mary K. Hendrickson, Philip H. Howard, Emily M. Miller, and Douglas H. Constance. https://farmaction.us/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Hendrickson-et-al.-2020.-Concentration-and-Its-Impacts_FINAL_Addended.pdf

[iii] Austin Frerick, Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry, Island Press, 2024.